The NIH refuses to reveal nearly 2,500 pages of records related to the National Toxicology Program’s decision to shut down its research on how wireless radiation affects human health.

Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, GETTR, Truth Social, X , Youtube

Editor’s note: This is the second in a three-part series investigating why the U.S. government ended studies on the biological effects of wireless radiation. Part 1 covered the expert opinion of John Bucher, Ph.D.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) refuses to reveal nearly 2,500 pages of records related to the National Toxicology Program’s (NTP) decision to shut down its research on how wireless radiation affects human health, according to an investigation by The Defender.

In January 2024, the NTP announced it had no plans to further study the effects of cellphone radiofrequency radiation (RFR) on human health — even though the program’s own 10-year, $30 million study, completed in 2018, found “clear evidence” of cancer and DNA damage.

In April 2024, Children’s Health Defense (CHD) filed requests to the NIH under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) to obtain records related to why the government shut down the research.

Miriam Eckenfels, director of CHD’s Electromagnetic Radiation (EMR) & Wireless Program said, “First and foremost, we want the science done.”

She said:

“If you find a smoking gun — as NTP did when it found clear evidence that wireless radiation was linked to cancer and DNA damage — you don’t just walk away. You find out why the gun was smoking. So the basic fact that the research was stopped is deeply disturbing.

“We believe the public deserves to know exactly why they decided to stop and whether the wireless industry had anything to do with it. Beyond that, we just care about the research getting started again.”

The reasons the NTP provided for ending the research aren’t good enough, according to Eckenfels. “It is the government’s job to protect the public from environmental harms, even if that is challenging and resource-intensive.”

“They can’t just say this is complicated, so we won’t even look at it,” she said. “The American public deserves better.”

The NTP is an “interagency program composed of, and supported by” the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and NIH, according to the agency’s website.

NIH hands over fewer than 400 pages of study protocol documents

CHD’s first FOIA request asked agency officials to hand over “all protocols, standard operating procedures, and other records describing the methods, procedures, and/or study goals of every study planned or conducted by DTT [Division of Translational Toxicology] to follow up on the rodent studies previously conducted by the National Toxicology Program.”

DTT is under the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). NIEHS is one of the NIH’s 27 institutes and centers. DTT scientists commonly work on NTP projects.

The FOIA didn’t allow CHD to simply ask the government why it stopped the research, said CHD Staff Attorney Risa Evans, who wrote the request.

“Unlike a deposition,” Evans explained, “the FOIA doesn’t give a right to ask questions or demand explanation for a decision. Instead, it allows members of the public to request agency records related to topics they want to investigate.”

The NTP’s 2018 study of 2G and 3G cellphone radiation found “clear evidence” of malignant heart tumors, “some evidence” of malignant brain tumors, and “some evidence” of benign, malignant and complex combined adrenal gland tumors in male rats.

After the study’s findings were published, DTT researchers began conducting follow-up studies, according to a February 2023 fact sheet.

The fact sheet said scientists had “overcome several technical issues” and were “now making progress” on four research goals. The goals included investigating the impact of wireless radiation on behavior and stress, conducting physiological monitoring — such as heart rate monitoring — and further evaluating whether wireless radiation causes DNA damage.

However, a January 2024 fact sheet said the NTP abandoned further investigation because “the research was technically challenging and more resource-intensive than expected.”

The NIH’s response to CHD’s FOIA request was mostly obfuscatory and failed to explain why the research was stopped.

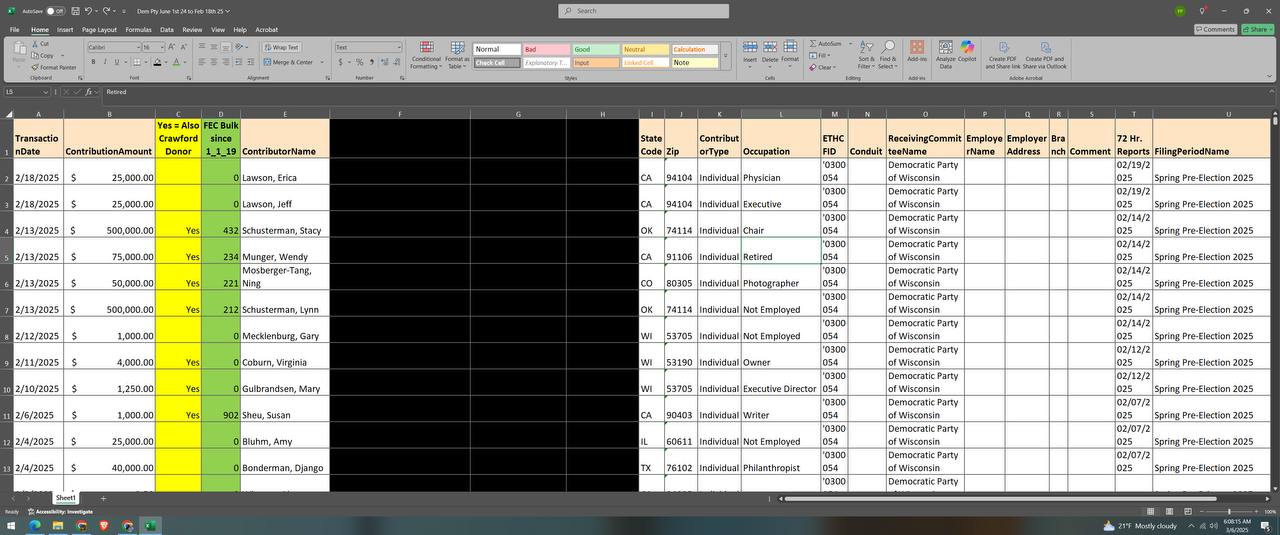

On Dec. 3, 2024, the NIH told CHD in a letter that it found 2,887 pages responsive to the request — but the agency released only 389 of them.

The remaining 2,498 pages were fully redacted.

“We are not surprised at the redactions,” Eckenfels said, “but find it disappointing nonetheless. The people deserve to know how our government agencies make decisions, particularly as it impacts their health. The redacted documents might have shed light on the decision.”

On Jan. 24, the NIH said in a letter that it would not release the redacted pages because they were exempt. According to the letter:

“Exemption 4 protects trade secrets and commercial or financial information that is privileged and confidential from disclosure.

“Exemption 5 allows for the withholding of internal government records that are pre-decisional and contain staff advice, opinions, and recommendations.

“Exemption 6 exempts from disclosure any records whose release would result in a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.”

On Feb. 13, CHD appealed the redaction decision. “It may be months before we get a response on our appeal,” Evans said.

W. Scott McCollough, chief litigator for CHD’s EMR & wireless cases, said CHD plans to wait and see how NIH responds to the appeal, given the new administration’s commitment to “radical transparency.”

Linda Birnbaum, Ph.D., who directed the NTP from 2009 to 2019 and oversaw its 2018 study, told The Defender she was “extremely disappointed” when she learned the NTP had stopped its wireless radiation studies.

“The original studies clearly indicated that there were some problems going on,” Birnbaum said, “and trying to get a better understanding was actually important.”

Records reveal details of ‘Tier 1’ follow-up studies

The 389 disclosed pages were presentation slides summarizing various aspects of the NTP’s wireless radiation research. The presentations were for academic conferences, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and the New Hampshire Commission to Study the Environmental and Health Effects of Evolving 5G Technology.

Dates of presentations ranged from 2018 to 2021. Some presentations were undated and failed to specify an intended audience.

Many slides only reiterated the findings of the 2018 study. However, some revealed information about the follow-up research.

For instance, one slide showed researchers planned a first round of follow-up studies labeled “Tier 1 studies” that included four experiments exposing small groups of rats to wireless radiation.

The slides stated that the Tier 1 studies tested the performance of a new system for exposing animals to wireless radiation.

The new exposure system involved building smaller radiation chambers than the chambers used in the 2018 study, according to John Bucher, Ph.D., who was highly involved in the NTP’s wireless radiation research.

However, the slides revealed that the studies were also designed to confirm DNA damage, investigate rodents’ behavior and stress responses to wireless radiation, measure rodents’ serum stress hormones, and evaluate rodents’ reaction to wireless radiation using video cameras.

The researchers also planned to examine the rodents’ brain, blood and liver cells.

Meanwhile, the NTP’s webpage makes no mention of studying biological outcomes. It states only that the studies were conducted to “assess the suitability of the new exposure system.”

Did the researchers modify the Tier 1 study plans to only test the suitability of the new exposure system? Or did they also test biological outcomes such as stress hormone levels and DNA damage as they originally planned?

These questions are left unanswered in the disclosed slides. “The answers likely lie in the pages NIH refused to disclose,” Eckenfels said.

Researchers planned to start the Tier 1 studies in July and August of 2020 and submit the results for publication in February or March of 2021, according to the slides.

However, COVID-19 likely delayed the plans, Bucher said.

So far, no results from the Tier 1 studies have been published, according to the NTP’s webpage. “The results will be made publicly available and posted on this webpage when internal reviews are finished.”

NTP hoped to work with FCC to measure people’s real-life RFR exposure

The 389 slides obtained by CHD also revealed that NTP had larger ambitions for its wireless radiation program before the research was halted.

For instance, one slide described additional studies beyond the Tier 1 studies that researchers planned to complete:

Another slide talked about “Developing a more comprehensive vision” in which the NTP would work with the FCC, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and other government agencies “to establish a program to better measure and characterize human exposures to RFR in ambient conditions in differing locations (schools, hospitals, parks, office buildings, residences, etc.).”

But that never happened.

The slides also revealed that NTP researchers knew there was great public interest in continuing RFR research.

For example, a slide listed multiple interested parties, including “governments of countries worldwide; American public; and likely the over 5 billion people worldwide that use cell phones.”

NTP researchers ostensibly were aware that investigating the links between wireless radiation, cancer and DNA damage was incredibly important. The same slide stated that “5G is worse than 2/3/4G” and that “RFR is not going away … maybe ever.”

Nonetheless, the NTP abandoned the work.

Devra Davis, Ph.D., MPH, a toxicologist and epidemiologist who reviewed CHD’s FOIA results, said that watching the demise of the NTP’s wireless radiation research has been like “watching a train wreck in slow motion.”

Davis served on the NTP’s board of scientific counselors in the 1980s when it launched. She is the founding director of the Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology of the U.S. National Research Council at the National Academy of Sciences.

“There were well-thought-out research plans that recognized the compelling need for this research,” Davis said. “The question is who made the decision to pull the plug on this, because the rationale for doing that was pretty flimsy.”

Davis added, “The worst thing that happens in times like these is that people start to censor themselves and stop doing work that might prove controversial and affect powerful interests.”

Suzanne Burdick, Ph.D., is a reporter and researcher for The Defender based in Fairfield, Iowa.

“© [Article Date] Children’s Health Defense, Inc. This work is reproduced and distributed with the permission of Children’s Health Defense, Inc. Want to learn more from Children’s Health Defense? Sign up for free news and updates from Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and the Children’s Health Defense. Your donation will help to support us in our efforts.

Bribes from the commercial producers of the devices generating this RF energy. Do wonder how serious this radiation damage is.